I didn’t talk much when I

was a child.

I stuttered and because of that I was incredibly shy, and this made speaking very difficult for me.

What does it mean to be a

child who stutters?

For me, it meant that when it was time for our daily read-aloud sessions in school, I panicked as I waited for my turn - and for my world to explode.

I would never raise my hand in class, because no sounds would come out of my mouth other than a repeating stutter. I tried to push words through my vocal cords that dread and terror had strung tight as barbed wire. I couldn’t give oral book reports and, in a million years, I would never join the drama club or the debate team or run for office or volunteer for anything where there was any speaking required whatsoever.

The hardest thing was saying my name and I would avoid it when I could. I was teased and made fun of and I tried to pretend that it didn't bother me. Just like in the movie, The King’s Speech, even adults would say things like slow down, relax, take a breath, or sometimes they’d say: "What’s wrong, don’t you know you own name?"

Or they’d look away, embarrassed, and that was the worst of all.

I was very much loved by my family and I was encouraged to be whoever I wanted to be. Long family hikes in the mountains and weekends on the beach at Cape Cod were fun and peaceful and nourishing and restorative. But there was no speech therapy in my small school in Massachusetts and I didn't know how to stop the teasing and most people outside of my family had no idea what I was going through because I was too ashamed to tell them.

I couldn’t answer the phone, much less

carry on conversations with relatives during their long-distance holiday calls,

and I couldn’t order food in restaurants because I’d have to say something

specific, and I couldn’t switch to an easier word, something that began with T, rather than the impossible Ms and Rs. I couldn’t speak to authority figures, like teachers and principals,

and although I could manage somewhat talking one-on-one to a friend (as long as

that friend was very kind and didn’t rush me or tease me and just listened) I

couldn’t talk in groups. This meant

sitting with the cool girls at lunch was impossible.

I was filled with so much shame and I wanted to become invisible and I learned how to do that by staying very quiet. Like Philippe in my newest novel, Chasing Augustus, who hides under his big coat, I got

very good at hiding.

Speech pathologists today call this the stuttering iceberg. On the top, the very small part of ice above water, are the repetitions, blockages and prolongations.

But underneath, is the big chunk of the iceberg, where the effects of stuttering hide: the guilt, shame, isolation, and utter hopelessness. I was this smart little kid

but people started wondering about that because I didn’t talk. And some

teachers who didn’t know any better stopped calling on me and although it felt

better in some ways to not be called on, I sat in the back of the class and it

made me even more alone and embarrassed and different than anyone else. And everyone expected a little less of me

each day. And I expected less of me,

too.

So what was the miracle that

turned my life around?

Books. Of course, I had no idea at the time what an

incredible and wonderful miracle they would become in my life, but they were my

solace, my escape, my greatest teachers.

I discovered Charlie and the

Chocolate Factory and Island of the Blue Dolphins and Heidi and Where the Red

Fern Grows and A Wrinkle in Time and Harriet the Spy.

I would check out as many

books as I could carry at my town library and walk home and head for my tree house and read the

afternoon away.

I found friends in books. I

found outspoken girls who weren’t afraid to speak their mind – children who

knew what it meant to survive. I wanted to be the girl in Island of the Blue

Dolphins, able to take care of herself on a deserted Island off the California

coast, and I wanted to be Billy, in Red Fern, selling bait, so I could buy my

own dogs. And when I read Harriet the

Spy, suddenly I knew I wanted to become a writer. After all, writers don’t have to speak!

What I began to realize from

reading all these books was that what I did was really hard – speaking was

really hard for someone like me – but I could become a survivor, someone who

didn’t quit.

So the second amazing and

wonderful miracle that happened was that even though I couldn’t communicate

verbally so well, I could communicate through writing. I started writing ALL

THE TIME and the door to speech was closed but the door to writing flew wide

open.

And the third miracle was that teachers started noticing my

writing and saying I wrote like a dream and boy couldn’t this quiet little kid

write, and they pushed me and encouraged me and believed in me.

Suddenly, in the sixth

grade, I had a voice! And I never stopped. I wrote fledgling short stories, tried my hand at novels, and wrote for our church literary magazine. One of my poems was published in a national church newspaper. My high school senior

English teacher loved my writing and she was so tough, but she believed in

me. And she is the one who said I really

did have the talent to go college as a creative writing major, and even though

I was still stuttering severely, off I went to college to write, because after

so much struggle, I had finally found something I was truly good at.

And in college I also found speech

therapy with an amazing private speech pathologist who applauded each step I

took. Over the next ten years she taught me how to speak fluently, and she also taught me how to walk away from the isolation and believe in myself.

Today, it is in writing that I find my life’s meaning. I faced so much adversity as a child, struggling to speak and

communicate with the outside world, and now I am able to write books about

transformation, about characters like Cornelia in Tending to Grace, who stutters, and Rosie Gillespie, in Chasing Augustus, who will never give up on her dog, not ever. They both face almost unbearable hurdles, but learn to push on, because they are strong and courageous and unsinkable.

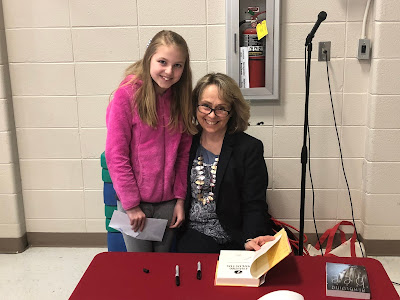

Today I feel blessed to write for children and I hear from kids from across the US and throughout different parts of the world. I get beautiful, uplifting, handwritten letters from children in my mailbox and each is a gift that I treasure. Like this one from a little girl in NJ:

“Your book changed the way I see the world and taught me so many great things. A rough start leads to a great end, and a great end throws the bad times away. Forget about it and just walk away with a heart filled with happiness.” Sincerely, Marie Nicole.

I've only begun to share the depths of my story over the last couple of years. And this is because that when I am brave enough to share my own story of transformation, the young writers in the schools I visit are more willing to dig deeper to tell their own stories.

I tell them: "We all have something to overcome, to

deal with, to grow through. Sometimes it’s on the outside

for the world to see, sometimes it’s hidden.

But it's universal that we all have something. With friends and family and teachers and mentors behind us, we can begin to rise and reach our potential. And if we reach our potential, we can help those

around us. And then we are life-givers and light-bearers."

I

never knew this as a child, but looking back at my life now I see that my

struggles helped shape me into the person I am today. I may not have gotten the voice I wanted when I was a young girl,

but I got a much bigger voice. When I was a child, I wouldn’t have known it was even possible.

Recently, my husband said, "Kim, isn't it something that the little girl with no voice grew up to have one of the largest of all?"